All equines are at risk of gastric and colonic ulcers and unfortunately, there is a high prevalence.

It has been estimated that a staggering 1 in 3 horses are diagnosed at some point in their life time, with foals being most susceptible due to having a more delicate stomach lining than the mature horse. Recent studies have shown that up to 90% of racehorses and approximately 67% of competition horses display some level of ulceration, however it is also common in leisure horses. Although not always preventable, there are ways to reduce the risk of ulcers occurring in your horse and ensure a healthy, efficient digestive system.

What are gastric and colonic ulcers?

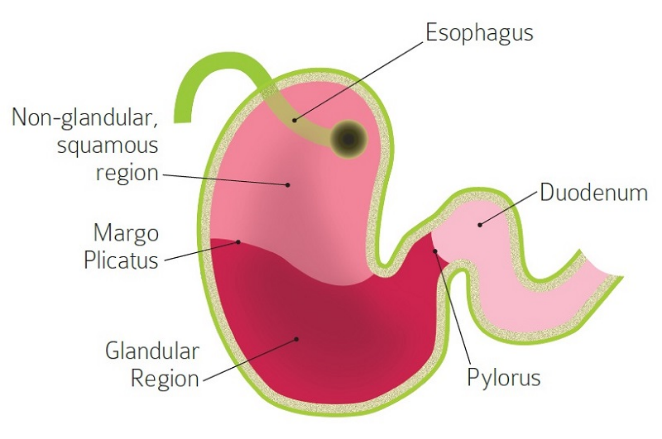

Gastric and colonic ulcers are painful lesions that develop in the lining of the stomach or hind gut and defined as a thinning of the lining of the gastrointestinal tract. The horse’s stomach is divided into two sections: a non-glandular ‘squamous region’ and a glandular region that are separated by the Margo Plicatus, a fibrous divide, and both sections of the stomach can be vulnerable to ulcers.

Glandular ulcers:

The glandular region is approximately two thirds of the stomach. The lining of the glandular region is protected by a thick mucus layer, containing glands which secrete active enzymes (pepsins) and hydrochloric acid that aids digestion by breaking down food, bicarbonates and mucus. Ulcers typically develop slowly in this region as a consequence of the mucous lining failing to protect the walls of the stomach.

Squamous ulcers:

The squamous region is the top third of the stomach and has very little protection from the hydrochloric acid and therefore more susceptible. Consequently, it is more common to find ulcers occurring in this non-glandular region. Ulcers here form quickly as a result of increased acid exposure to the tissue.

Colonic ulcers:

Colonic ulcers are the term given to ulcers developing in the hind gut. Although not as common as stomach ulcers, there is still a high prevalence with a study estimating up to 60% of performance horses having some level of colonic ulceration. These are far more difficult to diagnose, and your vet is likely to use a combination of methods such as blood work, and/or ultrasound of the right dorsal colon, based on clinical signs shown.

Why do ulcers occur?

There isn’t a definitive cause as to why ulcers occur, but research has indicated horses with restricted turnout and a diet of high starch feeds/low in forage are more likely to develop ulcers. Asthe horse is a trickle feeder and should be grazing for over 18 hours a day, he is constantly secreting gastric acid for digestion. However, if the stomach is empty for too long, the acid sits in the stomach and causes the abrasive ulcers. Forage has a natural acid buffering action, so therefore it is essential that the horse has constant access to forage at all times, whether that be grass or good quality hay.

What are the symptoms?

It is very important to consult your vet if you suspect your horse may be developing ulcers. The only way to make a definitive diagnosis is via an endoscope examination (gastroscopy). Some symptoms of gastric and colonic ulcers include:

- Inappetence

- Difficulty maintaining weight

- Loose droppings

- Recurring colic symptoms

- Behavioural changes

- Sensitive to pressure, particularly around the girth area

- Resistant to work

- Excessive recumbency

- A dull coat

- Poor performance

Feeding to reduce the risk of ulcers developing, and managing those after a veterinary diagnosis:

- Horses need at least 1.5% of their bodyweight in forage per day and as previously mentioned, a high fibre diet is essential, so it is important that every horse has access to good quality forage at all times. This will ensure that there is always forage within the stomach to buffer the acid and offer protection to the delicate lining as it has been shown that a horse left without forage for over 6 hours is 4 times more likely to develop glandular ulcers.

- It is often also a good idea to offer hay or feed a scoop of chaff prior to exercise. By ensuring there is forage in the stomach prior to exercise, you are reducing the risk of acid splashing and harming the non-glandular region of the stomach, which is often likely during fast or jumping exercise.

- If you provide your horse with a daily concentrate feed, split these into as many small feeds per day as possible, and mix with chaff to increase chewing and saliva production. By feeding small, frequent meals rather than one large concentrate feed a day, you will reduce the risk of the gastric pH become too acidic in between feeds.

- If additional calories are needed on top of a high forage/fibre diet, then oil is a great addition to the diet as it is a safe source of slow release energy and a better alternative to high starch and sugar feeds. Alfalfa and unmolassed sugar beet are particularly useful feeds for horses prone to ulceration, as they are both high fibre also high in calcium, which acts as an antacid.